Building a factory farmed future, one pandemic at a time

A wave of African swine fever outbreaks has been wreaking havoc on global pork production over the past decade, with ripple effects across the whole meat industry. Luckily this livestock disease is not a direct threat to human health, but a quarter of the global pig herd may have already been wiped out and the economic costs are running well into the hundreds of billions of dollars. Yet while small farmers have been decimated, the outbreaks are a windfall for transnational meat companies, and the companies that supply them. They are once again shamelessly using this pandemic, which they helped to propagate, as a political weapon to consolidate their dominance. A new approach to livestock diseases is urgently needed that protects small farmers, consumers and animals by dismantling the main source and vector of lethal pathogens-- Big Meat's factory farms and global supply chains.

Summary:

- The African swine fever (ASF) pandemic decimating pig herds in Eastern Europe and Asia is a product of today's globalised, industrial meat industry.

- The vast majority of pigs that have died from this pandemic are in factory farms and primary vectors in the spread of the disease include meat processing plants, movements of live pigs and animal feed supply chains controlled by large pig farming companies.

- The outbreaks are concentrated in geographic areas where small pig farms are being rapidly replaced by corporate pig farming operations.

- Governments and large pig farming companies have jointly defined responses to ASF outbreaks that protect these companies and penalise small-scale farmers.

- Big meat companies are making huge profits from the ASF pandemic and using it to consolidate their control over the global meat supply.

Duong Van Vu is one of thousands of Vietnamese farmers who risked everything to industrialise his pig farm. He took out loans to construct two confined barns, bought the top breed of piglets, and nourished his pigs with branded feeds sold by multinational corporations.

But in January 2019, several pigs at one of his barns in Dao Dang village fell violently ill. He thought it might be the feed making them sick, so he called the feed company. They did some tests and administered some medicines but his pigs got worse. So he called the local veterinary authorities. They took samples and sent them onwards to a lab. Those tests concluded that Mr. Vu's farm was Vietnam's first official case of African swine fever (ASF)-- a lethal pig disease that has killed up to a quarter of the world's pig population over the past few years.

It was a devastating moment for Mr. Vu. He lost all his pigs and was barred from restocking for a year. A few weeks later, the pigs in his other barn were culled when they started to show similar symptoms.1

Mr. Vu was perplexed. He'd done everything the veterinarians and company technicians had said he needed to do to keep his pigs free of diseases. He wondered if the disease may have been brought in by the traders who come to the village to buy pigs. After all, it's likely the disease was circulating in Vietnam unreported prior to the outbreak on his farm, as it had been detected in processed meats at around the same time.2 An equally plausible explanation is that it came in through the feed he purchased (see Box 1: Industrial feeds as a vector for ASF).

The reality is that there is little that Mr. Vu could have done to protect his pigs from ASF. Dao Dang village, like countless other villages suffering through this current ASF pandemic in Asia and Europe, was cajoled and coerced into a globalised chain of production, subjecting farms to the new and deadly diseases that this system brings with it. ASF is just the latest in a growing list of diseases that can ruin any one of these farms on any given day.

This connection between the expansion of industrial pig farming and outbreaks of ASF is often ignored. Fingers are instead pointed at small farmers and local traders, who are accused of poor hygienic practices.

“The main reason that you have African swine fever in China and Eastern Europe is that you have a lot of backyard farming in both parts of the world,” says Rick Janssen, president of the European Association of Porcine Health Management. 3

But the geographic path of this current ASF outbreak in Europe and Asia corresponds more with the aggressive build up of factory farms, contract production systems and export-oriented slaughterhouses over the past decade and a half. ASF outbreaks are especially concentrated in the frontier areas where the big pork companies have been expanding, integrating these areas once dominated by small farms and local markets into transnational pork supply chains and the global trade in live pigs and animal feeds-- two of the most important vectors in the spread of ASF.

The narrative matters: it determines not only how effectively ASF is dealt with but also who wins and who loses. With the current wave of ASF outbreaks, and other recent global livestock pandemics, the false portrayal of small-scale pig farmers as the conduits for the disease has favoured a response based on a corporate model of biosecurity that has decimated small farms and accelerated the expansion of factory farms and corporate control over the entire pork production chain (see Box 2: GRAIN's research into global livestock diseases).4

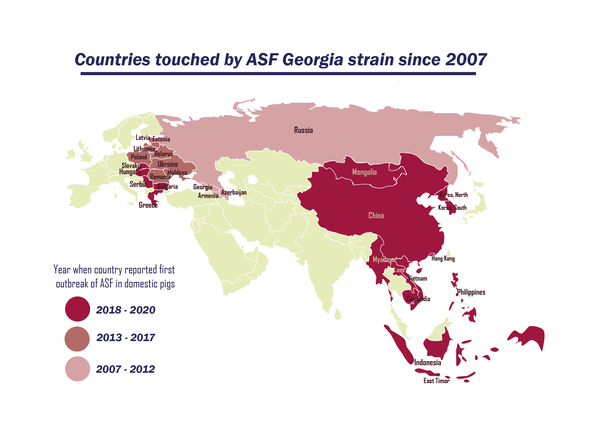

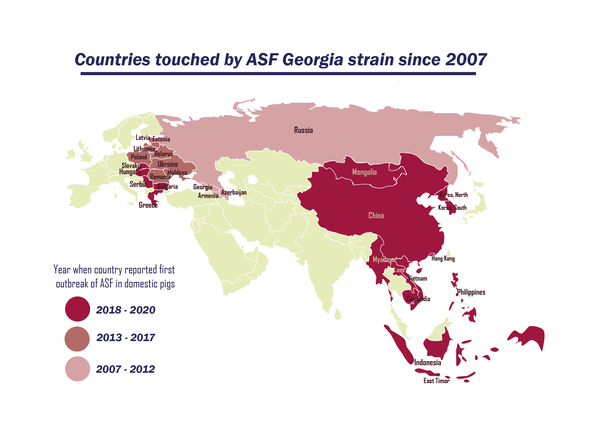

Map 1. Reported outbreaks of the ASF Georgia strain

ASF goes viral in Russia's factory farms

ASF's first encounter with domestic pigs occurred in Africa at the beginning of the 20th century, when it caused lethal outbreaks in the pigs of European settlers in Kenya. The disease has mostly stayed in Africa since then, but the improper disposal of contaminated meats by shipping vessels is said to have caused several periodic outbreaks elsewhere, in both pigs and wild boars. Each of these outbreaks outside of Africa were dealt with through mass culling campaigns, since no vaccine is yet available for the disease.

Box 1: Industrial feeds as a vector for ASF

ASF can contaminate animal feeds and survive processing, storage and transportation, and even hide out in the linings of commercial feed bags.5 Both Russian and Chinese authorities have identified industrial feed as one of the main vectors for ASF outbreaks in their countries.6 Moreover, China is a global supplier for several key ingredients routinely used in industrial animal feeds that are known to transmit ASF-- including vitamin supplements and proteins made from pig's blood.7 Despite the obvious disease risks, pig's blood collected from pig slaughterhouses, often referred to as "porcine plasma", remains an important ingredient in industrial pig feeds, which the animal feed industry has lobbied hard to maintain.8

The current wave of outbreaks of ASF outside of Africa began in the Eastern European country of Georgia in 2007. Prior to that, this particular strain of ASF had only been detected in Zambia, Madagascar and Mozambique. It's not known for sure how the disease reached Georgia; Georgian authorities speculate it came in from ship waste dumped near the port of Poti while Russian authorities blame a former Soviet bioweapons lab, which Georgia has operated since the early 2000s in cooperation with the US Department of Defence.9 In either case, the disease is known to have been circulating within the country, killing thousands of pigs, before it was officially diagnosed in early July 2007. One of these initial outbreaks occurred at the country's largest pig farm complex, which may explain how the disease spread so quickly across Georgia and into neighbouring countries.10

Box 2: GRAIN's research into global livestock diseases

GRAIN began working on global livestock diseases in 2006, when we launched a report on the global bird flu pandemic. That report punched a hole in the accepted wisdom, promoted by meat companies and international agencies, that the disease was mainly being spread by wild birds and backyard farms. It exposed the rapid rise of factory farms in Asia as the likely source of this highly pathogenic virus, and the global meat industry as the principal conduit for its spread. We wanted to help the small farmers and wet market traders challenge the punitive measures that they were being unfairly subjected to, and to push for an effective global response to the disease that would also prevent the industrial meat system from producing more such lethal diseases. Unfortunately this has, for the most part, not happened, and more outbreaks have occurred, notably the swine flu outbreak in Mexico in 2009. Sadly, our investigations into today's ASF pandemic read like a déja vu of the work we began over a decade ago.

Some of GRAIN's reports on livestock diseases:

Fowl play: The poultry industry's central role in the bird flu crisis, 2006: https://grain.org/e/22

Viral times - The politics of emerging global animal diseases, 2008: https://grain.org/e/614

A food system that kills - Swine flu is meat industry's latest plague, 2009: https://grain.org/e/189

Georgia has minimal veterinary services and pig farming is pretty much entirely handled by small farmers who let their pigs roam freely. Slaughtering and processing are also very much at a small scale and within local circuits.11 Yet, despite dire warnings from agencies like the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the ASF epidemic in the country was over within a year. No official outbreaks were recorded after, even though cases are suspected to have occurred subsequently, including a major outbreak at a new factory pig farm in 2014 that shattered the company's efforts to resurrect industrial pig farming in the country.12 A recent national survey of domestic pigs found no evidence of the disease.13

It is an entirely different story in the industrial pork producing regions of neighbouring Russia, where ASF struck next.

In the early 2000s, new companies, known in Russia as agroholdings, began buying up large areas of farmland and establishing massive pig farms in the southwest of Russia, near to the border with Georgia, as part of a national programme to develop agribusiness in the region. Much of this activity centred in Krasnador Kray, where pig production was still largely in the hands of small holder farmers.

The first ASF outbreak in Krasnador occurred at a large pig breeding complex owned by an agroholding.14 Russian authorities reacted quickly, culling all 6,800 pigs at the farm, and this appeared to work. The following year the disease was only detected in wild boars and in a herd of a dozen or so pigs at a small farm. But in 2010, ASF broke out in more agroholding pig farms, and things then escalated dramatically.

These agroholding operations were the perfect vector for the widespread dissemination of ASF in Krasnador and beyond-- sprawling sets of factory farms that generate huge quantities of manure, that move pigs, staff, feed and equipment constantly between locations, and that pump tonnes of meat into supply chains that stretch across the country and beyond. Even the culls used to stamp out the disease at these farms could easily spread it, as they involve the disposal of tens of thousands of contaminated pigs.

The agroholdings could not keep ASF out of their operations. Kuban Agro, an agroholding owned by a close friend of Vladimir Putin's and one of the largest pig farming companies in Krasnador, had two outbreaks at its farms in 2011 and another two in 2012, killing a combined 16,000 pigs.15 In 2016, its farms were hit again.16 Another agroholding owned by a Saint Petersburg businessman lost 45,000 pigs when its mega-barn had an ASF outbreak in 2012.17 Even the ultra-modern factory farm of the Danish company Dan-Invest AS was no match for the disease. In 2012 the company had an outbreaks that killed over 15,000 pigs, and then another in 2016 that killed 31,000.18

Between 2010-2012, ASF outbreaks destroyed over 255,000 pigs in factory farms in Krasnador. There were far fewer reported deaths in small farms, about 1,400.19 Yet despite the disproportionate presence and risk of ASF among the large pig farms, the Russian authorities, under pressure from the agroholdings, focused their crack down on small farmers.

Box 3: Can an ASF vaccine save the day?

A vaccine against ASF could go a long way to helping farmers, big and small, deal with ASF. Research, however, has languished-- partly because there wasn't enough economic interest in developing vaccines for an "African problem" and partly because the disease can mutate rapidly. Now, however, with a single strain of ASF causing massive losses on industrial pig farms in Europe and Asia, and threatening to hit North America, research into a vaccine is picking up.

Whether or not this increase in research will deliver a solution to small farmers could depend on how the race for patents plays out. There are already several patents on strains of the current ASF virus that is circulating in Europe and Asia. The Russian state veterinary lab has patents on virus samples it collected from Russian farms.20 The Pirbright Institute in the UK, which is the OIE reference lab that first assessed the Georgia samples, and the US Department of Defence's Plum Island lab in the US both used the Georgia ASF isolates to develop and patent attenuated strains of the virus that can be used for the development of vaccines.21 Other research labs in Spain, Canada, China and Vietnam are also hunting for their own patents for ASF vaccines.

The pharmaceutical companies will come in next, when these labs try to ink exclusive agreements for commercial development.22 Those negotiations would determine whether a vaccine will be accessible to the average small pig farmer.

All pigs on small farms, whether healthy or sick, were culled if they were within a five kilometre radius of an infected farm. In the case of the Danish farms, small farmers were banned from raising any pigs within a 25 km radius.23 And while the big farms received compensation when their pigs were culled, small farmers rarely were. These measures were part of a government policy for ASF designed “to decrease pig headcount in households and family farms [in Krasnador] by substituting them with other farm animals.”24

Other regional authorities followed the same line. In the Belgorod Oblast, where a fifth of Russia's pigs are raised, local authorities tried to buy up the entire supply of pigs from small farmers and even implemented a pre-emptive cull of backyard pigs before ASF entered the territory.

The policies pursued by Russian authorities were vigorously supported by the agroholding companies, whose executives portrayed themselves as victims of poor biosecurity practices on small farms.25 "The only way to reduce risks of ASF spreading is to ban the raising of pigs in small farms," said Maxim Basov, CEO of Rusagro, one of the country's largest agroholdings.26 At the time, Rusagro had not yet had an oubreak at its farms. But, a year later, in 2017, ASF hit one of its mega farms near the Ukrainian border. This farm supplied a company-owned pork processing plant in the Tambov Oblast that had just been approved to export pork to China.27

Russia's culling campaign and crack down on small farms did little to stop ASF from heading northwards into other pig producing areas or into neighbouring countries. The measures did enable the big companies to recover their production, but only at a tremendous cost to Russia's small farmers. The production of pork on small farms since the ASF outbreak began was cut in half, while production by big industrial pig farms doubled.28 The Russian approach to dealing with ASF was a disaster for Russian farmers that should never have been emulated in Eastern Europe, where the disease struck next.

ASF goes west

Once ASF started to spread within Russia, it was likely that neighbouring Ukraine would be next. Experts with the FAO and other animal health agencies cautioned that the number one risk was the preponderance of backyard farms along Ukraine's border with Russia. "The smallholder pig sector represents the highest risk for ASF introduction," warned the FAO in 2010. "If ASF were introduced into Ukraine, the first premises infected would most likely be smallholder low-biosecurity farms or backyard holdings." The FAO went on to suggest that small Ukrainian pig farmers should be encouraged to shift to rearing other animals or to grow crops instead.29

In mid-2014, ASF arrived in Ukraine as the FAO had predicted, near to the Russian border and at small farms that were likely infected by contact with wild boars. But these small outbreaks were quickly dealt with, and it would take another year before the disease reappeared. This time, however, it happened at a massive farm, far from the Russian border, just outside the capital Kyiv, where companies had been aggressively building up factory pig farms.

In early August 2015, a shipment of 277 pig carcasses tested positive for ASF at a slaughterhouse outside the city of Poltava.30 The meat, which had arrived a couple of weeks prior, was traced back to a farm outside of Kyiv, 300 km from the Poltava plant, that was owned by the Kalita Agrocomplex, one of the country's largest producers of pork.31

Box 4: What makes this pig disease African?

ASF is called African swine fever because that's the name white settlers in Africa gave it, when their pigs started dying of a mysterious disease that looked a lot like classical swine fever. But it is also true that ASF is mainly endemic to large parts of Africa, causing sporadic and sometimes devastating outbreaks.

ASF has become more of a problem in Africa over the past three decades as pig production has doubled and trade has increased. It has shifted from a disease spread mainly by host ticks and wild pigs to a disease spread through pig farming and the pork supply chain. While the reported losses of pigs from ASF over the past 4 years are nowhere near those of Asia or Europe, ASF is still one of the main impediments to pig production on the continent.32

This was no ordinary farm. It was the country's largest fattening barn, holding over 60,000 pigs. Contaminated meat originating at the complex was likely sent out far and wide across the country, before the disease was officially registered. Moreover, the farm itself, which is situated within a larger complex of horticultural farms and a feed mill, generated multiple pathways for ASF to amplify and spread if left to fester for a few weeks, as it apparently had.

There have been over 350 reported outbreaks of ASF in Ukraine since the Kalita outbreak, hitting both large and small operations. One of the more recent and dramatic occurred on August 18, 2019 at a massive factory farm owned by the Danish company Zythomir Holding and backed by Nordic development banks.33 The outbreak destroyed 95,000 pigs, nearly 2% of the entire national pig herd. It was more evidence that Danish factory farms, which claim to practice the highest levels of biosecurity, are particularly susceptible to ASF (See Box 5: The failure of Danish-owned farms to stop ASF).34

Romania's first brush with ASF also took place on backyard farms, to the north of the country in 2017. This initial outbreak was rapidly controlled, but a year later a series of outbreaks erupted at large farms in the southeast, generating a glut of dead pigs that the local authorities could not properly dispose of.35

Box 5: Danish-owned farms are no match for ASF

In 2012, a truckload of 700 Danish breeder pigs heading to a factory farm owned by Rusagro was intercepted at the Polish border by Russian customs authorities. Investigations uncovered that 37 pigs had died en route and had then been dumped along the roadside in Poland, without notification of the incident to the Russian border authorities or the provision of the required test results for disease.36 The Russian government, fearing that the pigs may have died from ASF, threatened to ban imports of Danish pigs.

The truck load was one of many that are sent to Russia and other Eastern European countries every day from Denmark. Danish pig companies export around 10,000 breeding pigs a year to Russia, accounting for about 40% of the total. The pigs pass through Poland, which now imports over 6 million Danish pigs each year.37

But Danish pig companies are not merely taking control of Eastern Europe's live trade in breeder pigs; they also now own many of the region's largest pig farms. The Danish companies say their operations are modern and more environmentally friendly than the dilapidated farms of the former Eastern Bloc, and they claim to have the highest standards for biosecurity. But locals are outraged by the pollution generated by the Danish mega farms and the aggressive tactics these companies use to establish them.38 The reality is that Danish companies operating in Eastern Europe are having a hard time managing diseases, particularly when it comes to ASF. Outbreaks of ASF at Danish-owned farms accounted for about a quarter of all the pig deaths from ASF outbreaks in Eastern Europe that were reported to the OIE between 2016 to May 2019.39